Fig. 1: Thomas Phillips, Portrait of Sir John Franklin, 1828. Oil on canvas,768 mm x 514 mm. National Portrait Gallery, London. Bequeathed by Lady Franklin’s niece, Miss Sophia Cracroft, 1892. NPG 903.

Sir John Franklin is best known in Australia for his role in this country’s colonial history, in particular his attempts to foster education and culture in Van Diemen’s Land while Lieutenant-Governor of that distant imperial outpost between 1837 and 1843.[1] His intrepid and unconventional wife, Jane, Lady Franklin, is also remembered for founding a museum on the outskirts of Hobart, and for her tendency to undertake challenging journeys. Not only did she explore Tasmania’s wildness, she also made the overland trip from Melbourne to Sydney, and even crossed the Tasman to New Zealand, the latter two trips without Sir John.[2]

In the Victorian period, however, Sir John Franklin achieved world renown as one of the great arctic explorers, undertaking three expeditions in search of the fabled ‘Northwest Passage’, before his posting to Van Diemen’s Land. On his return to Britain, he was appointed leader of one further venture north, and gradually became the focus of intense international speculation, following the mysterious disappearance of his expedition (the two vessels Terror and Erebus and their crews) into the polar wastes. The grisly remains of the men, their possessions and a written message recording Franklin’s death and the crews’ desperate situation were eventually located after repeated searches over many years. Indeed, the full realization of the expedition’s tragic fate only ensured John Franklin’s reputation as a courageous but doomed “hero of discovery”.[3] It also raised to celebrity status his redoubtable wife, who had never given up the search for her husband and had in fact funded several voyages from her own resources.

Fig. 2: Pierre-Jean David D’Angers, Sir John Franklin, 1829. Bronze medallion, 124 mm in diameter. National Portrait Gallery, London. NPG 5435.

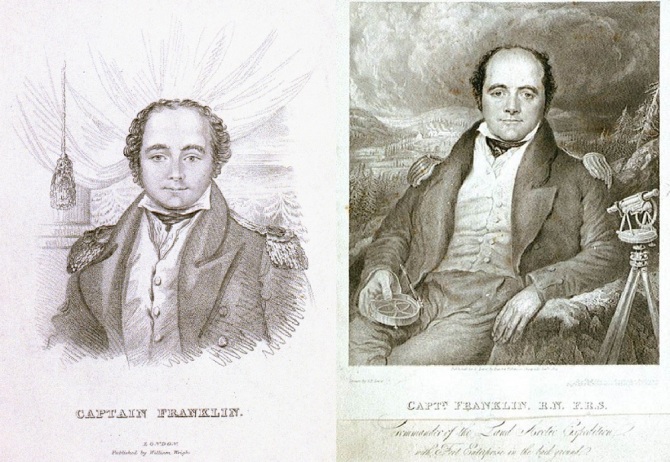

Unsurprisingly, there were many contemporary portraits produced of the heroic Sir John Franklin. Some of the earliest depictions appeared in the frontispieces of various accounts of his voyages, including his own best-selling book, Narrative of a Journey to the Shores of the Polar Sea, in the Years 1819-22 (London, 1823). That his celebrity extended into mainland Europe is indicated by a bronze medallion of his profile executed in 1829 by the leading French sculptor, David D’Angers [fig. 2]. Other portraits include those by Thomas Phillips, William Derby and John Jackson, R.A., as well as the widely circulated image by Joseph Mathias Negelen of Franklin in naval uniform, which was reproduced in numerous print versions. Franklin’s final voyage was even commemorated in the new medium of photography, through Richard Beard’s famous daguerreotypes of the expedition’s leader and officers. Portraits could almost be said to mark every stage of Franklin’s life; he himself was very conscious of their role in shaping perceptions and recording history and his wedding present to his first wife, Eleanor Porden, was a portrait of himself painted by Thomas Phillips [fig. 1].[4]

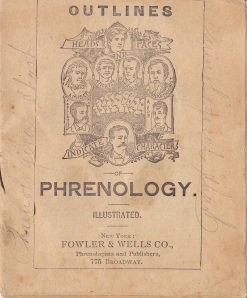

Despite the disastrous conclusion of his last expedition – with all lives lost – Franklin retained his reputation as a courageous leader who died within sight of achieving his goal. This widespread perception was chiefly due to the determined efforts of his wife, who moved heaven and earth to have him acknowledged as the discoverer of the Northwest Passage, and to Franklin’s biographer, C. R. Markham, who ‘rewrote both the Franklin expedition and the search missions as chivalric romances’.[5] Evidence of his high posthumous status can be found in a variety of late Victorian texts. One noteworthy—and until now unpublished—example is the presence of his portrait in a small pamphlet published in New York in 1884 entitled Outlines of Phrenology [fig. 3]. The pseudo-science of Phrenology was highly popular during the nineteenth century and sought to relate the shape of a person’s head to traits of his or her character. In this pamphlet, the shape of Franklin’s skull and features were interpreted as an example of the ‘Temperaments Combined’, which underlined the very positive ideal that Franklin was seen to represent. The accompanying text elaborates further:

‘By the Temperaments are understood the states of the body and mind with respect to the predominance of different qualities. They are divided into (1st) Motive or muscular, (2d) Vital or nutritive, (3d) Mental or thinking, instead of Nervous, Bilious, Lymphatic and Sanguine. Those who have the Motive temperament are powerful, tough, enduring, fond of pursuits which require energy and authority. Those who have the Vital are fond of pleasure, enjoy good living, active occupation, and social life. The Mental temperament gives sensitiveness, mental activity, desire to think and study, and the moral feelings and refining sentiments are generally well marked in those who have this temperament in predominance. When the temperaments are combined in equal or nearly equal proportions, the person is adapted to study, labor, or business of any kind.’[6]

Fig. 4: Anon, Outlines of Phrenology, New York: Fowler & Wells, 1884: Portrait of Sir John Franklin.

The line engraving of Franklin’s head and features that illustrates this passage [fig. 4] would appear to be derived from the etched portrait by William Wright [fig. 5]. This is in turn indebted to G. R. Lewis’s portrait of Franklin as ‘the Commander of the Land Arctic Expedition’ [fig. 6], one of the canonical images of Franklin as brave polar explorer. For an audience in the 1880s, then, a phrenological reading of Franklin’s portrait as representative of his outstanding abilities—being ‘adapted to study, labor or business of any kind’—reaffirmed the cult of Franklin as a hero destined for greatness, rather than one whose efforts would end in failure.

Fig. 5 (left): William Wright, Captain Franklin. Stipple engraving. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. Fig. 6 (right): F. C. Lewis, Captn. Franklin, R.N. F.R.S., Commander of the Land Arctic Expedition with Fort Enterprise in the background, 1 Jan 1824. Stipple engraving after drawing by G. R. Lewis. National Portrait Gallery, London.

One further example of the influence of the pseudo-science of phrenology upon Victorian thinking is provided by Lady Franklin herself. Even if she did not fully believe its claims, she was very willing to adopt the language of cranial measurement when discussing people’s appearance and character. Thus, in 1838, when Jane Franklin sent a written description to her sister of her portrait by the colonial artist Thomas Bock [fig. 7], she commented humorously:

Fig. 7: Thomas Bock, Portrait of Jane, Lady Franklin, 1838. Chalk on paper, 34 x 30 cm. Queen Victoria Museum & Art Gallery, Launceston. QVM.1928. FD.497.

‘… would you believe it that I am having my portrait taken again to please Mrs Maconochie, who insisted on my sitting (for her) to an artist here, who does these things tolerably well and who [is] going on a visit to Sydney and perhaps not return here. This time I am to be without a cap, and it is three-quarters face in that position which is to bring to light very conspicuously, by Mrs Maconochie’s express desire, my two great bumps of causality.’[7]

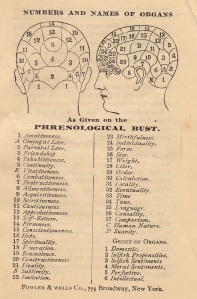

The ‘bumps of causality’ to which Jane Franklin refers had been identified by phrenologists as being located on the upper sides of the brow, as can be seen in the illustration in the 1884 Outlines of Phrenology [fig. 8]. Quite simply, causality was the ability to understand cause and effect, to think logically and abstractly, and was therefore one of the main reflective faculties. Of course, the degree to which Jane Franklin and Mary Maconochie actually believed such phrenological interpretations is beside the point. Their casual reference to ‘bumps’—indeed, the deliberate positioning of Jane’s head so that the light fell on her rather prominent forehead and all that feature so flatteringly implied—clearly demonstrates how central such thinking had become in any discussion of portraiture in the early Victorian period.

© Alison Inglis, School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne.

[1] Kathleen Fitzpatrick, ‘Franklin, Sir John (1786–1847)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/franklin-sir-john-2066/text2575, accessed 7 December 2013.

[2] See Alison Alexander, The Ambitions of Jane Franklin, Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2013.

[3] Samuel Mossman, Heroes of Discovery: Magellan, Cook, Park, Franklin, Livingstone, Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1868.

[4] Ken McGoogan, Lady Franklin’s Revenge, London: Bantam Press, 2007, p. 78.

[5] Andrew Lambert, Franklin, Tragic Hero of Polar Navigation, London: Faber and Faber, 2009, p. 315.

[6] Outlines of Phrenology, New York: Fowler & Wells, [1884].

[7] Lady Franklin to Mrs Simpkinson, Hobart, 21 June 1838, Royal Society of Tasmania papers, University of Tasmania, RS 16/10, cited in Andrew Sayers, ‘Thomas Bock, Draughtsman’, in Diane Dunbar, Thomas Bock: Convict engraver, society portraitist, Launceston: Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, 1991, pp. 19-20.

Hi Alison, I just came on this essay, with pleasure. A delicate comment on the belief systems of the colonists. And very entertaining to boot! John K